One of the marchers, captured by a photographer, wore a Johnny Cash T-shirt.

Johnny Cash’s gospel versus the temptations of nationalism

by: Paul O’Donnell

Jan. 10, 2020 (RNS) — Marching through dark streets under torches, the mob proudly displayed their swastikas, shouting “Heil, Hitler” and chanting the chilling refrain, “Blood and soil! Blood and soil!”

One of the marchers, captured by a photographer, wore a Johnny Cash T-shirt.

This wasn’t 1930s Germany. This was Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017.

The association of Johnny Cash with the hate-filled, white-supremacist “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville drew a sharp and public rebuke from the Cash family. Cash’s daughter Rosanne posted a passionate note on her Facebook page on behalf of herself and the other Cash children.

Under the heading “A message from the children of Johnny Cash,” Rosanne described her father as “a man whose heart beat with the rhythm of love and social justice. … His pacifism and inclusive patriotism were two of his most defining characteristics. He would be horrified at even a casual use of his name or image for an idea or a cause founded in persecution and hatred. … Our dad told each of us, over and over throughout our lives, ‘Children, you can choose love or hate. I choose love.’”

When you think of the music of the Man in Black, you mostly think of the music where Cash speaks up for the poor, the struggling and the disenfranchised, songs that “beat with the rhythm of love and social justice.”

But Cash was an outspoken patriot and he loved America, and his patriotism often made the gospel messages found in his music vulnerable to distortion and misappropriation, in exactly the same way that patriotism and nationalism of all sorts can distort and twist the gospel. Nationalistic nostalgia can lead us into some dark, troubled waters. A neo-Nazi could end up wearing your T-shirt.

No song better captures this dynamic than “Ragged Old Flag.” The song, from the 1974 album of the same title, recounts a narrative of loss and decay. The flag — and the nation it represents — has been damaged.

The problem with this “narrative of injury” is that it conjures up feelings of resentment, causing us to peer anxiously across the political aisle, our backyard fences and our national borders as we search for the culprits who are hurting America. The image of the ragged old flag — a damaged America — creates suspicion and paranoia, and that fear breeds intolerance and hate.

We can keep the gospel witness of Johnny Cash free from the temptations of patriotic nostalgia by focusing on how his music spoke up for the people the American Dream has left behind. The music of Johnny Cash is at its best, artistically and theologically, when he calls for an “inclusive patriotism.” When Cash sings “These are my people” in his love song to America, we keep in view his advocacy for Native Americans, the prisoners cheering in Folsom and San Quentin, the Great Depression farmers in Arkansas and the African American artists he invited on “The Johnny Cash Show” in the early 1970s.

For us to avoid the trap of nostalgia, the songs we sing about America must be complicated and often critical. Such criticism is an expression of love and an act of patriotism. My favorite lyric of Cash’s in this regard comes from his little-known song “All God’s Children Ain’t Free,” from the album “Orange Blossom Special”: “I’d sing more about more of this land, but all God’s children ain’t free.”

I don’t want to suggest that Cash fully reconciled the political tensions and inconsistencies we observe in his music and life. But Cash’s music would be hopelessly vulnerable to patriotic nostalgia if albums like “At Folsom Prison” and “Bitter Tears,” an album of Native American protest songs, didn’t exist.

Our capacity for prophetic critique flows out of these conflicts and tensions — the gap between national aspiration and national failure, between national pride and national guilt. When this capacity for criticism erodes we lose what Walter Brueggemann has called “the prophetic imagination,” the ability to imagine our nation standing under the judgment of God.

To be sure, this will be harder or easier depending upon how you feel about America, but cultivating a capacity for prophetic critique is the task of every Christian, especially when you live in a nation you are proud of and grateful for.

As Ralph Gleason wrote of Cash’s political witness during the tumultuous years of Nixon, race riots and Vietnam: “He’s struggling. He’s not perfect, but he’s trying. He loves this country but he’s trying to keep that from meaning he hates some other.”

In our own troubled, polarized political climate, none of us is perfect, and most of us are struggling. Like Johnny Cash, a lot of us are trying to love our country without that meaning we have to hate somebody else. We are grateful for our freedoms, but we are also crying out for “a more perfect union.”

In the end, I think Cash himself summed it up best: We’d “sing more about more of this land, but all God’s children ain’t free.”

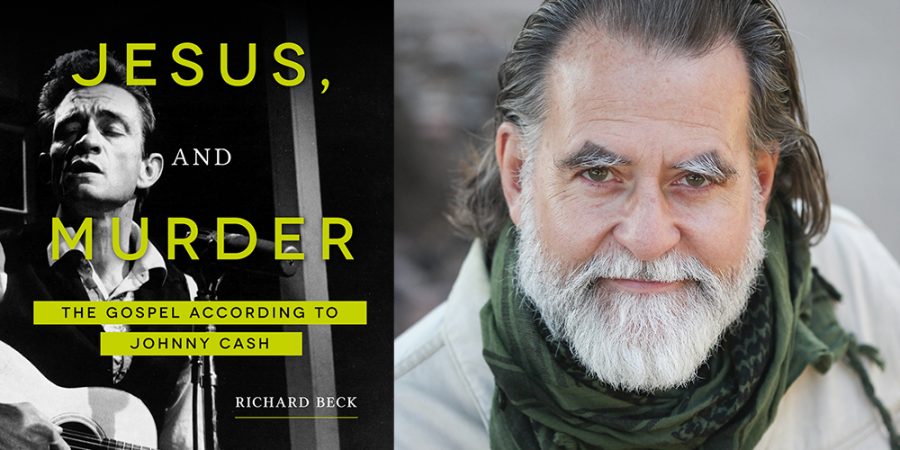

(Adapted from Trains, Jesus, & Murder: The Gospel According to Johnny Cash by Richard Beck. Copyright © 2019 Fortress Press, an imprint of 1517 Media. Used by permission. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Read about books at XPian News… https://xpian.news/category/books/

Comments are Closed