“Desmond Tutu: A Spiritual Biography of South Africa’s Confessor,” Battle delves into Tutu’s religious formation...

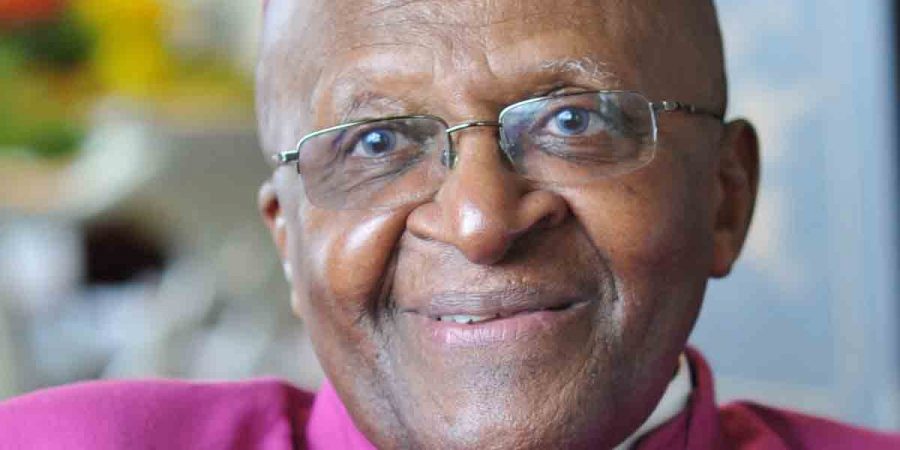

New book explores how Desmond Tutu’s Christian mysticism helped unite a nation

But Michael Battle, a professor at New York’s General Theological Seminary who directs the Desmond Tutu Center there, wanted to draw attention to the particular Christian vision that animates Tutu. It’s a subject Battle has devoted much of his professional life to — ever since he was a Ph.D. student at Duke University in the early 1990s.

In his new book, “Desmond Tutu: A Spiritual Biography of South Africa’s Confessor,” Battle delves into Tutu’s religious formation — he was baptized a Methodist, but as a teen came under the influence of a white Anglican monk who impressed on him a mystical Christian vision grounded in prayer and silent contemplation. Those practices served a larger vision of community that ultimately sought integration between the spiritual and the secular.

Into that Christian mystical tradition, Tutu also wove in the African view of “Ubuntu,” a term meaning “humanity” but more broadly a collection of values Africa’s Black people view as making people authentic human beings.

That African-infused Christian mystical tradition was powerful enough to help topple apartheid and unite a riven nation. Tutu is probably best known for his role as chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, in which he oversaw South Africans confess to the crimes of the apartheid era and begin to mend the relations between them.

Battle calls Tutu a saint, and his love for Tutu, who officiated at Battle’s wedding and baptized his three children, is evident.

Religion News Service spoke to Battle about his book and about how Tutu’s life’s work exemplifies the ways deep faith can undergird transformational leadership on the world stage. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

First, how is the archbishop’s health?

He’s doing well. He’s living in an intentional community where he gets wonderful care. He’s 89 years old and still mobile. But he doesn’t travel at all internationally. He was not infected by the (coronavirus) pandemic. So all things being equal, he’s doing well.

What drove you to meet and write about Tutu?

I was trying to make a decision about my dissertation. I had an epiphany walking through the corridor of Duke Divinity School when a professor of spiritual direction asked me, “What do you want to write on?” Tutu immediately came up. Tutu was on sabbatical at Emory University that year. I was bold enough to go down and have an audience with Tutu and pitched my idea to do a Ph.D. on him and take his theology seriously. The first thing he said was, “Let us pray.”

Subsequently, I went to South Africa. I thought I’d stay in a youth hostel and do research in the libraries and maybe get some interviews. But Tutu invited me to live with him. They didn’t have a chaplain for him. I was in the ordination process in North Carolina, but I was able to finish the process there and Tutu ordained me a priest. I was his de facto chaplain. I had full access to all his writings — even things he wrote on napkins.

You start your book by saying Tutu is a saint. You acknowledge that’s a controversial thing to say as a biographer. So why say that at the outset?

I felt the authenticity living with him for two years and seeing his public persona. Here’s someone who has integrity behind the scenes, just as much as he has in the public limelight. To me, that’s really the hallmark of what it means to be holy. The Christian church has always tried to hold up the institution of saints not just as an exclusive men’s club, but as exemplars of what it looks like when you’re held accountable for a well-lived life. Tutu is an exemplar of that.

You say Tutu is a mystic and that helped him articulate a vision of community that is also the image of God. Explain that.

In our day and age, we’ve lost that mystical sensibility because of the institutional church. Institutions have a job of making things that are transcendent, practical, pragmatic, linear, methodical. But for most of church history, the way we understood being a church and having access to God was through the mystics, the monks, the saints. Christian mysticism is important because it taxes the Christian imagination to move beyond the binaries we often find ourselves in, such as Protestant and Catholic, conservative and liberal. Christian mysticism is always trying to tear down these idols we’ve built. In institutionalized westernized Christianity, mysticism may seem irrelevant but in fact it’s extremely important in terms of the Christian imagination for things like restorative justice.

Tutu merges his Christian vision with the African understanding of Ubuntu. Is that something South African society was able to weave into Christianity?

Ubuntu is a word in the system of languages known as Bantu that means “to be human.” But it carries a whole lot more. To be human is to understand humanity through the other. So the proverbs “I am because we are” and “A person is a person through other persons” — that’s the connotation of what it means to be human. You can’t know what your gifts are unless there’s a community to make those concepts intelligible. The way Christians understand God is very similar to that concept of Ubuntu. The concept of the Trinity and how you make sense of that one God (in three persons) is through that very same proverb: A person is a person through other persons.

The subtitle of your book is “A spiritual biography of South Africa’s confessor.” Why is confession so central to Tutu?

A confessor is the priest who hears the confession. It comes out of the Roman Catholic Church and the rites of reconciliation.

When all is said and done, Tutu will be remembered for chairing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, where as long as you confess what you did between 1960 and 1994 you could be forgiven and granted amnesty. Nelson Mandela asked Tutu to be chair of that. Tutu made it work. It was a unique practice of a nation-state in which people came and disclosed secrets in a public arena. In many ways it healed South Africa and prevented it from becoming a quagmire of cyclical violence.

Can Tutu’s example offer lessons to other conflict areas around the world?

On the macro level, we have a virus of the North Atlantic slave trade and the hierarchy of existence that occurred when Black people were viewed as subhuman. Unless there is some public way in which the institutions that have benefited from the North Atlantic slave trade can admit the benefits they received, publicly and systematically, then we’ll keep the virus of police shooting Black men and the virus of hindering Black people from voting. The United States could benefit from a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. We have some segments doing that — George Washington University is giving free tuition to descendants of slaves. Instead of doing this in a piecemeal way, we could do it more systematically, like South Africa did.

Read more news at XPian News… https://xpian.news

Comments are Closed