“I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us,” Douglass said, “I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary!"

Opinion: The Fourth of July: Time to celebrate or lament?

On July 4, 1776, there were already hundreds of thousands of slaves in Britain’s American Colonies and in some, such as Virginia, Blacks made up more than half of the inhabitants. Black people were the economic engine for produce, construction, manufacturing, home economics and more.

Among the reasons given for why the colonists insisted on independence from Britain, little attention is paid to the rumors in the Colonies at the time that John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore and governor of Virginia, had, along with other governors, learned that England was considering an end to the transatlantic slavery.

At the same time, as historian Sylvia R. Frey has pointed out, there was a brewing fear among the white colonists that their own cries of “Liberty” would provoke a Black slave uprising.

After the victory, at a meeting in Williamsburg, Thomas Jefferson broached the idea of freeing the slaves, but his idea met enormous resistance. If the slaves were freed, it was reasoned, the economic foundation of the newly developing nation would sputter.

One wonders how the Declaration of Independence could declare American freedom from England but evaded freeing slaves. How could the ruling white colonists fight for freedom, sometimes alongside Black men, hundreds of whom fought in the Revolutionary War, and remain numb to the possibility of liberty for the slaves?

It can only be understood if we accept that white colonists considered Black people less than human beings. Blacks were only good for what whites wanted from them. Black people mattered, but only as slaves; as human beings, Black lives did not matter. Black life, liberty and pursuit of happiness, therefore, were not germane to the fabric of the North American project.

This mindset still plagues the United States today.

As the country evolved, laws further ingrained a culture of the privileged and the underprivileged, systemized slavery, and socialized racial bigotry. The former colonists turned their newfound national freedom into an unscathed systemization of Black oppression. By the early 1800s, prohibitions against slaves marrying each other were already in place, and punishments for slaves trying to gain freedom had been intensified.

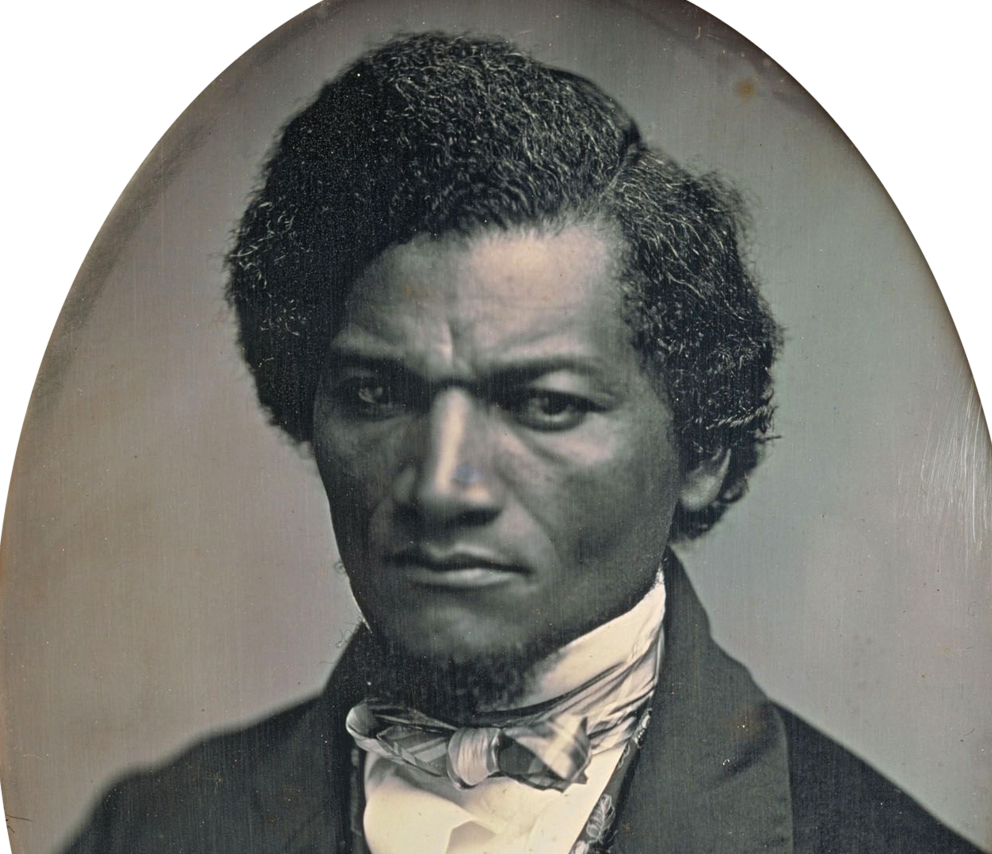

Seventy-six years after the American Revolution, Frederick Douglass praised the insurmountable patriotism, heroism and intelligence that the leaders of the American Revolution possessed and critiqued their blatant contradiction that plagued the same revolution. As for so-called Christians, Douglass called them “hypocrites.” His speech “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?,” delivered to the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society in 1852, expounds upon the undeniable hypocrisy that weaved its way through the fabric of early American development.

“I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us,” Douglass said, “I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common.

“The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me,” he continued. “The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

In the wake of the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Sandra Bland, Atatiana Jefferson, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Rashard Brooks and so many others, this generation has awakened to the blatant reality that, even in the 21st century, Black life still does not matter.

And yet, the Black fight for life, liberty and pursuit of happiness remains. Leading up to this year’s Fourth of July, the national cry of “Black Lives Matter!” has gone global. That in itself, perhaps, is reason to celebrate. But as long as structural inequality — in education, justice, health care, finance and other systems — and disregard for Black pain and suffering are still part of this nation’s identity, the question remains: Should this be a time of celebration or lamentation?

(Antipas L. Harris is the author of “Is Christianity the White Man’s Religion?: How the Bible is Good News for People of Color” and associate pastor at The Potter’s House of Dallas. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Read more news at XPian News… https://xpian.news

Comments are Closed