[A]n Indian-Canadian named Ravi Zacharias was beginning to see that Western culture was fast becoming a "post-Christendom" society...

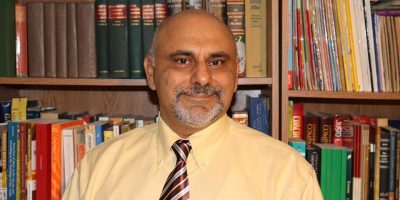

Opinion: How Ravi Zacharias changed the way evangelism is done

Even those who did not profess Christianity would come prepared for my preaching with beliefs in the existence of God, in an afterlife, and with respect, at least, for the Bible. I could simply point to biblical texts and say, “Here is what you must believe,” and most people responded either “yes” or “no.”

A very few people would ask, “Why believe in God? Or trust the Bible? Or believe in an afterlife?” In an evangelism course, I had been trained not to try to answer questions like this but to ask if I could simply proceed with my gospel presentation to the end. The implication was if someone asked, “why should I even believe in God?” that they nonetheless really did believe in God and would be able to respond to the call to repentance and faith. This approach to evangelism was characteristic of the church throughout the Western world.

Even in those days, however, an Indian-Canadian named Ravi Zacharias was beginning to see that Western culture was fast becoming a “post-Christendom” society, where Christianity no longer felt true or even plausible. He saw that people would no longer simply be showing up in church, that the church would have to go out to them. Most importantly, Zacharias recognized that the leading cultural institutions were no longer instilling those basic religious beliefs in people, particularly in the young, and especially among leaders in society.

RELATED: Christian apologist Ravi Zacharias dies of cancer at 74

Thus, the church could no longer avoid the why questions, what in Christianity is called apologetics. Ravi recognized that what had once been a “boutique” niche, something for intellectuals and people who “went in for that philosophical stuff” — had to become part and parcel of how Christianity was presented to a watching world.

The reason Zacharias, who died May 19 following a brief battle with cancer, was able to foresee the trends that few others did had to do with his own background as the product of several worlds.

Zacharias was born in India in 1946 and immigrated with his family to Canada 20 years later. As an Indian raised in the East, but academically trained in the West, he was an outsider and an insider to multiple cultures. As such, he was able to see social changes more clearly and could also cross significant cultural divides. His Eastern storytelling often connected with those searching for meaning in the West, while his Western philosophical framework challenged the more relativistic outlook of many in the East.

The global character of his impact may seem unusual to secular Western observers, but contrary to popular portrayals, Christianity is not a Western and white phenomenon. Zacharias embodied the global, transcultural nature of the Christian faith.

Zacharias had also been both an atheist and a Christian believer. Born into a nominally Anglican family and being surrounded by a plurality of religious traditions — each loudly proclaiming a different spiritual path — Zacharias as a young man was left with a sense of purposelessness. He professed to not believe in anything. The despair led him to attempt suicide at age 17, swallowing poison he had taken from a university chemistry laboratory.

This certainly ended Zacharias’ old life, but not in the way he had intended. He wound up in a hospital for a few days, and during his stay someone introduced him to the words Jesus gives to his disciples in the Gospel of John: “Because I live, you also will live.” Sparking spiritual hope in Zacharias for the very first time, these words would come to define his life. He became a Christian and immediately dove into Christian literature and thought.

Zacharias would also take his first steps into what would become his lifelong calling: sharing his faith with others. He started preaching almost immediately across India and then continued when he moved to Toronto in 1966. He had a startling impact in both places.

His ministry often took him in a different direction from many of his peers. In the 1980s, an era of prominent “televangelists,” Zacharias saw the need to engage those with intellectual objections to Christianity. In 1983, Billy Graham invited Zacharias to address a historic gathering of evangelists in Europe. He was struck by how few preachers in that world had adapted to the new reality of the post-Christian West. After that meeting he came to see apologetics not as a sideshow for a small group of devotees, but as a major part of how Christianity was offered to audiences around the world.

Ravi Zacharias International Ministries (RZIM), founded in 1984, put into practice a new way of doing Christian communication. Its team of speakers and writers from all corners of the world began to spread Zacharias’ vision of commending Christ to culture-makers across the globe. Now numbering around 100 speakers in 15 countries on nearly every continent, the very shape of the ministry Zacharias has left behind reflects the cross-cultural contours of the faith he spent 50 years commending.

RZIM also fostered the Oxford Center for Christian Apologetics, based in Oxford, England, which offers a variety of programs for training workers in evangelism and apologetics. (Most recently, the Zacharias Institute, a training and conference center in Atlanta, was launched.)

Voices as diverse as Lesslie Newbigin and Francis Schaeffer had been urging the parochial Western church to wake up and see how fast society was becoming post-Christian and calling the church to adapt to the new mission field. Ravi saw the same realities, but, instead of speaking to the church about what to do, Ravi led the way to doing it.

It would be a mistake to think that Ravi spoke to intellectuals using rational arguments. At bottom, Zacharias did not see “apologetics” as a series of intellectual moves. For Zacharias, it was not about winning the argument, but engaging the person. Even in today’s “cancel culture,” where disagreement typically leads to polarization and vitriol, Zacharias had a unique gift for disarming hostility with gentleness, humor and respect.

Today it can be very hard to imagine public discourse in which questions are welcomed, disagreement does not threaten and each person is spoken to with quiet but informed confidence, and with the utmost dignity and respect. Ravi Zacharias believed and proclaimed, but more importantly, showed that following Jesus makes this possible.

In the final years of his ministry Zacharias was perhaps most in his element in the very place many Christians would fear to tread — a secular university campus — enjoying the back and forth as dozens of students lined up to ask their questions about (and often raised their objections to) his faith.

Even as Zacharias moves on, the Christian church in the West should move toward this vision for our public life together, remembering, as Zacharias put it, that “love is the greatest apologetic.”

A memorial for Zacharias will be livestreamed on May 29, at RZIM.org/RaviMemorial.

(Timothy Keller is founder of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Manhattan, and author of numerous books, including “The Reason for God.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Read more news at XPian News… https://xpian.news

Comments are Closed