At 39, Wilson-Hartgrove has spent the better part of his life breaking out of the white evangelical cocoon he grew up in.

Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove wants white evangelicals to reckon with the Bible

While they were rehearsing, he checked in on José Chicas, an undocumented immigrant who has been living for more than two years in a clapboard house the church owns next door.

Wilson-Hartgrove then hopped into his gray Honda minivan and drove five miles north to collect a few boxes and suitcases belonging to a man named Gordon.

Gordon, who did not want to give his last name, was recently released from prison. He’s now the newest resident of the six-bedroom house of hospitality where Wilson-Hartgrove and his family live in community with some friends.

For Wilson-Hartgrove, the life of an activist and writer is all-consuming. A son of the South — Wilson-Hartgrove grew up in the small town of King, North Carolina, about 95 miles west of Durham — he remains both devoted to the region and one of its staunchest critics.

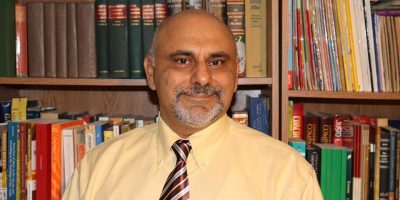

At 39, Wilson-Hartgrove has spent the better part of his life breaking out of the white evangelical cocoon he grew up in. He settled in a poor, mostly black neighborhood and preaches in a predominantly black church. He and his wife, Leah, have adopted an African American boy. In recent years, he’s traveled the country with the Rev. William J. Barber II, the charismatic civil rights leader.

Anyone following Barber’s trajectory may recognize the 6-foot-6 Wilson-Hartgrove towering beside his mentor. The two first met when Wilson-Hartgrove was 16, and they have worked together since.

They have been especially close over the past decade. Barber called Wilson-Hartgrove the scribe for the Poor People’s Campaign that he founded, serving as the main author of the national movement’s printed materials.

“Every prophetic movement needs a scribe,” said Barber. “Jeremiah had Baruch,” he added, referring to the biblical prophet and his scribe. “Jonathan is our Baruch.”

But Wilson-Hartgrove is also a writer in his own right, and his books are intended for white evangelicals who he hopes might be persuaded to abandon what he called in his 2018 book “slaveholder religion.” The term is not uniquely his and he uses it to explain today’s historic parallels with 19th century faith and politics.

Slaveholder religion is Wilson-Hartgrove’s shorthand for a faith that turns a blind eye to systemic racism and instead prizes obedience and law and order, while idolizing capitalism and corporate interests.

Wilson-Hartgrove’s most recent book, “Revolution of Values: Reclaiming Public Faith for the Common Good,” is his 13th. In it, he tells the stories of people harmed by poverty, voter suppression, cruel immigration policies, mass incarceration, ecological devastation, militarism.

Wilson-Hartgrove hopes to convince white evangelicals they have misread the Bible and help them discover, as he has, the black freedom movement’s understanding of Scripture as focused on justice and freedom.

Wilson-Hartgrove hopes to convince white evangelicals they have misread the Bible and help them discover, as he has, the black freedom movement’s understanding of Scripture as focused on justice and freedom.

He worries the religious right’s focus on political power has coincided with the rise of the so-called nones, those who claim no religious affiliation.

“I think that’s a real concern for Christian communities,” he said. “A lot of people don’t want to have anything to do with the church.”

A gradual rebirth

As a boy, Wilson-Hartgrove dreamed he might one day be president.

Born into a family of Southern Baptists in a town 23 miles from Mount Airy, the fictional Mayberry of the Andy Griffith Show, Wilson-Hartgrove grew up believing that Jesus was a Republican and that America was on the right side of history.

In high school, he served as a page to South Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond, an outspoken opponent of integration and civil rights.

Wilson-Hartgrove said his rejection of that white Christian worldview was gradual. He never had a crisis of faith.

“But I did come to realization at the end of my time in D.C. that the way I had been taught to live out this faith didn’t seem like good news to me,” he said.

Barber played a role in Wilson-Hartgrove’s transformation. The two first met when Barber spoke to North Carolina’s Youth Legislative Assembly when Wilson-Hartgrove was a member.

After that speech, Wilson-Hartgrove invited the African American preacher to speak at his high school’s baccalaureate service — an invitation Barber accepted with some trepidation.

“I knew the history of white supremacy in that area,” Barber said. “My brother went with me. It was a little unnerving.”

Wilson-Hartgrove went on to attend Eastern University near Philadelphia, which defines its core values as “faith, reason and justice.” At the time, sociologist and Baptist minister Tony Campolo was on the faculty. Among Eastern’s graduates are Bryan Stevenson, the noted death penalty lawyer depicted in the new film “Just Mercy,” and Shane Claiborne, the activist and founder of Philadelphia’s The Simple Way, a house of hospitality.

At Eastern, Wilson-Hartgrove met Leah Wilson, a Californian whose father, Jonathan Wilson, is a theologian and Baptist pastor. The young couple married and came to Durham, where Wilson-Hartgrove enrolled at Duke Divinity School.

In 2003, during the U.S. invasion of Iraq, the couple traveled to that country and Jordan as part of a Christian peacemaker team. On their way to Amman, the Jordanian capital, one of three cabs carrying the group was hit by shrapnel and landed in a ditch. The Iraqis who stopped to help took them to the town of Rutba, where they were treated at a makeshift hospital.

The hospitality they received there was life-changing. When they returned to Durham they rented a sagging bungalow in the predominantly black neighborhood of Walltown and called it the Rutba House. They welcomed neighbors in need of a meal or a place to stay. In those days, drive-by shootings and street drug deals were common and Wilson-Hartgrove would canvass the neighborhood on foot, praying with anyone he met.

The Wilson-Hartgroves adopted a black boy, JaiMichael, whom they met when he was in foster care. They have two more children, Nora, 10, and Nathan, 5.

In time, Wilson-Hartgrove was invited to join the neighborhood’s mostly black St. John’s Missionary Baptist Church as an associate minister. The house next door to the church became the site of Wilson-Hartgrove’s School for Conversion. The school is modeled after Tennessee’s Highlander Center, known for training many of the leaders of the civil rights movement. It runs after-school and mentoring programs and has a small library of books by and about figures in the American freedom struggle. Most of Wilson-Hartgrove’s income comes from the school.

The neighborhood is far more diverse now. Over the past 20 years neighborhoods close to Duke University have gentrified with newer suburban-like two-story homes where smaller homes once stood.

The Wilson-Hartgroves have moved with their larger family into a newer and bigger home donated to them by a local builder. But they remain committed to the neighborhood, volunteering with the local community association and hosting monthly neighborhood potlucks.

“Jonathan is very much part of the neighborhood,” said Gann Herman, who chairs the School of Conversion’s board and lives nearby. “It’s one of the things I admire the most about Jonathan and the School of Conversion is how rooted it is in the neighborhood.”

A national stage

In 2013, Wilson-Hartgrove’s call took him beyond his immediate neighborhood.

North Carolina Republicans had gained control of both chambers of the Legislature and elected a Republican governor, Pat McCrory, the year before. With complete control of the legislative and executive branches, Republicans passed restrictions on abortion, refused Medicaid expansion, cut unemployment benefits and adopted restrictive voting laws that were eventually overturned by the courts.

On April 29, 2013, Barber, then president of the NAACP’s state chapter, led a protest to the state Legislature building in Raleigh to call attention to the attacks on the poor. Seventeen of the protesters — including Barber — were arrested for disrupting the Legislature’s deliberations.

That protest led to the start of the Moral Mondays movement that took root in North Carolina and led to more than 1,000 arrests over several years. When protesters returned to the Statehouse the first week in May 2013, Wilson-Hartgrove was among them.

Barber decided in 2018 to focus more on national change and launched the Poor People’s Campaign — a revival of Martin Luther King Jr.’s final campaign to highlight poverty and the plight of the poor in a nation of riches.

Wilson-Hartgrove went on the road with Barber to help spread the message.

In his latest book, he tells about his travels to El Paso, Texas, where he waded in the Rio Grande waters to help unite an immigrant woman living in the U.S. with her family on the other side of the river in Ciudad Juárez.

He also recounts a visit to Nashville, Tennessee, where he befriended a former death-row inmate who spent 20 years in prison for a crime he did not commit. And he tells the story of a trip to the Arizona desert, where he met with San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation leaders fighting to protect Oak Flat, a sacred patch of land 40 miles from their reservation.

Through each encounter, he tries to illustrate how U.S. policies have harmed individuals and groups he met.

Wilson-Hartgrove’s last two books were published by InterVarsity Press, known for its willingness to take on controversial subjects with a more diverse author pool than other U.S. evangelical publishing houses.

“Anytime you are telling stories of wading in the water between Texas and Mexico, you’ll have blowback,” said Jeffrey Crosby, IVP publisher. “But we went into it with eyes wide open, fully committed to supporting Jonathan and the book through whatever comes our way. We believe he’s thoughtfully wrestled with the issues and the way Scripture informs the issues.”

One place where Wilson-Hartgrove has had a harder time busting what he calls “slaveholding religion” is at Liberty University — home to Jerry Falwell Jr., President Donald Trump’s best-known evangelical supporter.

Two years ago, Wilson-Hartgrove, Barber and others published an open letter challenging Falwell to a “peaceful debate” about Christian teaching at Liberty University. A few months later, both Wilson-Hartgrove and Barber led a revival at a high school near Liberty.

At that time, Falwell stifled efforts by the Liberty student newspaper to cover the event. He also had campus police send a letter to Shane Claiborne, a participant, threatening fines and jail time if he visited the Liberty campus.

But last month, Liberty announced the opening of the Falkirk Center for Faith and Liberty, a think tank intended to “play offense” against efforts by liberals to water down Judeo-Christian values — in the words of its leader, Charlie Kirk. One of the center’s first acts was to court Wilson-Hartgrove to a discussion of “Was Jesus Christ a socialist?”

In the days leading up to Christmas, Wilson-Hartgrove and Barber held a few phone calls with Liberty administrators to negotiate a time where they could hold that discussion.

“I’m not going to argue that Jesus was a socialist,” said Wilson-Hartgrove. “But yes, I want to have that conversation.”

Wilson-Hartgrove doesn’t necessarily want Christians to embrace his own lifestyle and politics. But he does want evangelicals to reckon with the ways the Bible has become captive to the white experience in America.

On Christmas Day, Wilson-Hartgrove, his wife and children spent the morning as they always do — singing carols outside Central Prison, a maximum-security facility in Raleigh that houses the state’s 143 death-row inmates.

The carolers, numbering about 100, sang “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” and “Jingle Bells.”

After each carol, they shouted in unison to the inmates, who may, or may not, have seen or heard them: “Merry Christmas,” “Happy Hanukkah,” “Happy Kwanzaa” and “Feliz Navidad.”

Shouting across divides isn’t Wilson-Hartgrove’s strong suit. He’d much rather preach, teach and write in a quieter, conversational tone. But he’ll take what he can.

“Jesus said, ‘I was in prison and you visited me,'”said Wilson-Hartgrove. “It’s also a way we remember how Christ promises to be present to us.”

Read more news at XPian News… https://xpian.news

Comments are Closed