New book links the decline of religious authority to the end of empathy

Many, that is, with one striking exception: white evangelicals.

When it comes to racism, immigration or even public health, polls show white evangelicals appear numb to any effort to improve the welfare and well-being of others.

RELATED: No race problem here: Despite summer of protests, many practicing Christians remain ambivalent

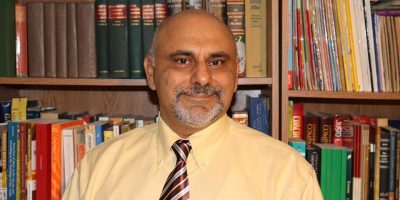

In his new book, “The End of Empathy: Why White Protestants Stopped Loving Their Neighbors,” John Compton, a political science professor at Chapman University, tries to explain how American Protestants moved from championing social reform to stubbornly resisting it.

His answer points to the decline of religious authority and the rise of individual religious believers, who, given the choice, prefer not to trouble the tranquility of their middle-class suburban lives.

The book covers a wide swath of 20th-century history, including the rise of the Social Gospel movement, the evangelical emergence, the revolution of the 1960s, the cratering of the mainline and ultimately the evangelical embrace of Donald Trump.

Religion News Service caught up with Compton to talk to him about the lessons from his book. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You begin your book by talking about the social incentives that once made belonging to a church so important in the early 20th century. You explore that through Max Weber’s observation about church as sect. Explain that a bit.

Weber was a giant and arguably the founder of sociology. He visited the U.S. in 1904 and spent some time touring the country. What he noticed is that people in the U.S. were very mobile. They uprooted and moved to new places frequently. In this very uprooted mobile society, people had to have some way of vouching for their character and reliability. He came to believe churches performed this role. If you wanted to be a member of a Baptist or Methodist or Presbyterian church, you had to demonstrate you were a reliable person; that you weren’t in debt or had an alcohol problem, etc.

Once you became a member of a church that vouched for your character, it made it easier to get a loan or to get a room in a boarding house. That dynamic is really important to understanding the influence of mainline Protestant religious leaders during the first half of the 20th century.

Obviously, the dynamic Weber observed in 1904 starts to peter out in the middle of the 20th century. But the political significance of that is these churches and their leaders had some degree of clout, vis-a-vis their members. If people want to get into your church, you have the ability to shape their worldview and press certain social and political views on them.

You write that people now self-select into congregations based on their political views and that clergy no longer have the same kind of influence over people in the pews. Does self-interest drive everything?

That’s the central argument of the book. The real pivot of 20th-century Protestant political involvement happens in the 1960s when there’s a general collapse of religious authority. Right up to the 1960s, the mainline Protestant churches are still pretty effective in mobilizing their members on behalf of political causes. I show how Northern white Protestant churches were very influential in pushing through the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

But by the time you get to the late 1960s and early 1970s, there’s a collapse of religious authority. People start leaving the mainline Protestant churches in droves, particularly young people — the same kind of upwardly mobile young people who were the backbone of the mainline Protestant churches. What you get is the emergence of this completely different religious environment. It’s a free market. People are picking churches not based on what will help advance my career or raise my standing in society, but simply on what message do I find appealing? It becomes more about entertainment, it becomes more about catering to people’s preexisting views and prejudices.

That’s why we see the explosion of megachurches, which arguably gets started in Southern California, where the mainline Protestant infrastructure was the weakest. They’re preaching a politically conservative message that says the Bible doesn’t ask you to do anything in terms of reaching out to the poor or the helpless. It certainly doesn’t authorize the government to redistribute wealth on behalf of the marginalized.

But ironically, those very evangelical churches that critiqued the mainline Protestants’ involvement in social justice causes lost their authority, too, right?

That’s what many people fail to understand about the modern evangelical movement. You see a lot of stories where it’s portrayed as a movement that has very powerful leaders and the rank and file wait to see who the leaders will endorse in politics or what causes they’ll endorse. But the so-called leaders have very little clout.

We see this every few years when some supposedly powerful evangelical leader will come out on behalf of a cause like combating climate change or something that’s not part of the normal conservative agenda. One of two things happens: They either get nowhere and renounce the position they took or they get shoved to the margin of the movement. That’s been the pattern since the 1980s.

I tell the story of Carl Henry, the longtime editor of Christianity Today. He’s generally thought of as this very politically conservative figure. And it’s true he was pretty conservative. But he also talked about the need to protect the environment and he talked about racial inequality being a major problem. He helped build up the evangelical movement but then when we get to the 1980s, he discovers that once religious authority has collapsed, no one is really interested in his message. He’s pushed to the margins while people like Jerry Falwell Sr., who are throwing conservative red meat to their followers, are much more influential and important.

A lot of evangelicals will contest what you say and insist they do work toward social issues. How do you respond?

I point to two or three recent examples of where important people and institutions in the evangelical movement came out on behalf of not traditionally conservative causes, like immigration reform, climate change, increasing foreign aid programs. In each of these examples, the leaders got so much pushback from the rank and file that they had to ditch the initiative.

Look at the immigration reform push which was really big in 2013 and 2014, where all these evangelical institutions came out for immigration reform, like the Southern Baptist Convention and the major professional organization representing evangelical colleges. And yet, at the end of the day, public opinion polls showed absolutely no movement on behalf of rank-and-file evangelicals. There’s no authority to change people’s minds on hot-button political issues. Evangelicals don’t have the institutions or the kind of socioeconomic clout that mainline Protestants had in the mid-20th century. That’s why it’s very hard for evangelical leaders to even marginally push against the views of rank-and-file churchgoers.

Where does that leave the prophetic voice?

You certainly have people on the religious left critiquing American society in a prophetic way and calling for reforms. You do have maverick evangelical leaders who come out occasionally with prophetic stances. But what’s different today is that it’s not clear religious leaders have the power to change minds.

Did the evangelical movement to privatize faith and view it as primarily about salvation help precipitate that?

Yes, absolutely. I recount in the book Billy Graham’s 1957 crusade in New York City. It was a hugely powerful event that went on for weeks and was covered on TV. Reinhold Niebuhr, who is the most famous theologian and Christian ethicist in the country, published a series of op-eds in which he says, hold on a minute. The kind of Christianity that Graham is pushing is going to be a disaster for American society because it strips Christianity of any concern for social ethics.

Graham’s argument is, if you come to Jesus, you’re less likely to be a racist and maybe we can end segregation that way. Niebuhr’s argument is, look, that’s not going to happen. People are inherently selfish. They’re inherently good at rationalizing their own preexisting prejudices. So if you strip all concern for social ethics out of Protestantism, you’re just going to be left with a bunch of people who are even more convinced of the righteousness of their preexisting views. At the time, people thought Niebuhr was a jerk. But if you look at the long view, history has proved him correct.

People talk now of the rise of the religious left. Is there any indication it’s making any kind of dent or seeing a resurgence?

I would love to see the religious left revived. I’m a little skeptical of how much clout they really have. People who respond to the religious left are already thoroughly left-leaning in their politics. In that case, it makes me wonder how much religion is really adding to the story. What would be fascinating to see is if this movement starts attracting people from more conservative religious backgrounds, and if they do more than preach to the choir, so to speak. But given the kind of weakness of the underlying institutions and the lack of socioeconomic pull that existed in the mid-20th century, I’m just doubtful that’s going to happen.

Read more news at XPian News… https://xpian.news

Comments are Closed